By Heather King - May 2013

PAPER CITATION

Rule, A. C., Stefanich, G. P., Boody, R. M., & Peiffer, B. (2011). Impact of adaptive materials on teachers and their students with visual impairments in secondary science and mathematics classes. International Journal of Science Education 33(6), 865–887.

This paper reports on changes in teacher attitudes toward visually impaired students following a yearlong programme that provided funds for adaptive resources, supplies, and equipment. The context framing this study is that special education teachers often lack knowledge of science and mathematics content. Conversely, many science and mathematics teachers lack confidence and competence in engaging young people with disabilities. Perhaps as a consequence of these factors, people with disabilities are notably absent in STEM fields (Bonetta, 2007). This study centers on teaching visually impaired students at the secondary level, but the key finding—that all learners benefit from adaptations designed to include students with disabilities—will be relevant to educators working across the spectrum of special education needs.

The authors begin with a short review of current policy and legislation regarding the education of disabled students. The authors note the work of Kumar et al. (2001), who found that students with visual impairments reflect the same spectrum of cognitive abilities as do their peers without visual impairment. Their reduced participation, the current authors note, is due to low teacher and parent expectations, fragmented resources, and teachers’ lack of professional preparation to use non-visual teaching methods. More positively, however, Rule et al. highlight prior research that points to the value of collaboration between visually impaired students and sighted peers. The research also emphasizes that teachers can help visually impaired students to become more independent.

Rule and colleagues studied 15 secondary science or mathematics teachers and 13 visually impaired students. A questionnaire probing the teachers’ attitudes toward students with disabilities was administered at the beginning and end of the funded programme. The teachers were also asked to record both their anticipated and actual experiences during the year. Finally, the teachers wrote narratives to document particular challenges and successes that they and their students faced.

The statistical analysis of the responses showed that teacher attitudes changed considerably over the course of the year. They felt better able to work with the students and considered this work to be less of a challenge. The greatest change in teachers’ perception involved their realisation that increased funding was needed for students with special needs. Ten out of the 12 teachers who completed the post-programme questionnaires reported that students with visual impairments had been just as successful in mathematics and science as their peers. The teachers also reported that having a student with visual impairment had helped them become better teachers for the whole class. For example, one teacher commented that “any time you can provide math students with hands-on activities, their motivation and retention of the material increases” (p. 883). Indeed, research in other fields has pointed to the benefits of letting learners work with manipulatives and other tactile materials. Adding to the range of sensory inputs helps to support students’ mental constructs.

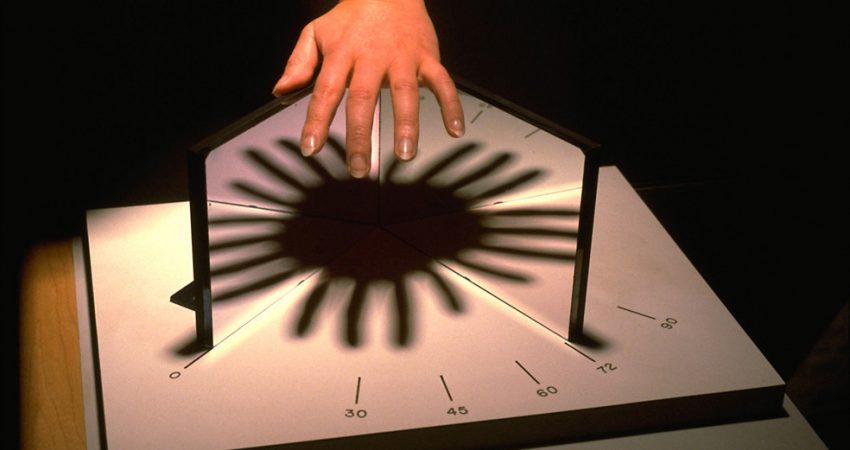

The paper lists a number of strategies that the teachers adopted during the year. These included, for example, using large tactile models to illustrate cell organelles and sticking symbols for chemical elements onto a Velcro board so that students could practice balancing equations. The authors also note the benefit of accommodations teachers made such as providing extra time, emailing presentations to the students in advance, and carefully selecting their vocabulary to ensure clarity of communication.

A caveat: The adaptive support and accommodation were not always well received by the students. Several teachers commented that their visually impaired student did not want to be marked out as different from peers. As a result, the teachers had to be subtle in changing their practices. However, in some cases the accommodations became mainstream as teachers recognized that the resources for the visually impaired were beneficial to all learners.

This paper shows that, with appropriate resources and equipment, teachers can support learners with disabilities to engage with mathematics and science. It also shows how educators’ perceptions of teaching students with disabilities can change. The authors suggest that their findings reflect a new and arguably better understanding of equity: Equity does not consist of offering identical experiences for all students. Rather, certain students need specialized materials in order to have equitable opportunities to learn.

Informal science educators may be particularly interested in and keen to respond to the paper’s recommendation that teachers should organize more field trips; many students with disabilities have few opportunities to visit informal settings, yet these spaces can offer a wealth of sensory experiences.

References

Bonetta, L. (2007). Focus on careers: Diversity – Opening doors for scientists with disabilities. Science, 318, 1161–1164.

Kumar, D., Ramasamy, R., & Stefanich, G. (2001). Science for students with visual impairments. Electronic Journal of Science Education, 5. Retrieved from http://ejse.southwestern.edu/article/view/7658/5425 30 April 2013.